The last post was all about mending cloth, and was full of words. This one has more pictures.

While I was compiling these examples, I was struck by how beautiful they all were, and then by how unintended most of that beauty was. The original owners and menders, for the most part, probably weren’t thinking so much of the visual outcome, at least for the utilitarian pieces, but about the solidness of the mend.

I also had a thought about something I read somewhere a long time ago, I think it might have been in Madhur Jaffrey’s autobiography. In it she recounts how her mother would regularly take all the items in the kitchen and ritually clean them and bless them for their service. This is something I sometimes do too, I hadn’t really thought about its spiritual dimension until I read Jaffrey’s book, but I had been doing it and reading that little anecdote made me realise that there is a grace in acknowledging the service of something by taking care of it.

Stretching that even further, I am not at all religious, if I had to pick a side I would say I am an animist - I believe everything has a soul (images of me as a tiny child holding my father’s hand and looking up at him as he explains that God lives in everything, in rocks, in the grass, in the river we were walking to. My father remains a damaged Catholic but he somehow inspired me to be what he always wished he could!). As a small child I used to rescue damaged things, it started with stuffed toys but quickly grew to encompass cracked crockery, broken machines, and torn clothes. I was convinced they could feel, and I hurt on their behalf that they were being discarded.

Recently, in a Guardian article on Marie Kondo, the journalist mentions Kondo’s animist Shinto religion, and the belief that an inanimate object could obtain a soul after 100 years of service. If this is so, (and I don’t have much trouble believing it, for after all we are all made of the same star-dust), then the vast majority of pieces that pass through my hands definitely have souls. I know they do because sometimes I can feel it.

{I’ve just reread that paragraph and realised that I have been rescuing damaged items since I was about five. Clearly this is a vocation!}

And I thought that if someone’s rough cobbled mend of 100 years ago is someone else’s rare treasure today, then what excuse have we got today to throw things out when we could be creating future works of utilitarian art with them, even if our needle skills are positively awful.

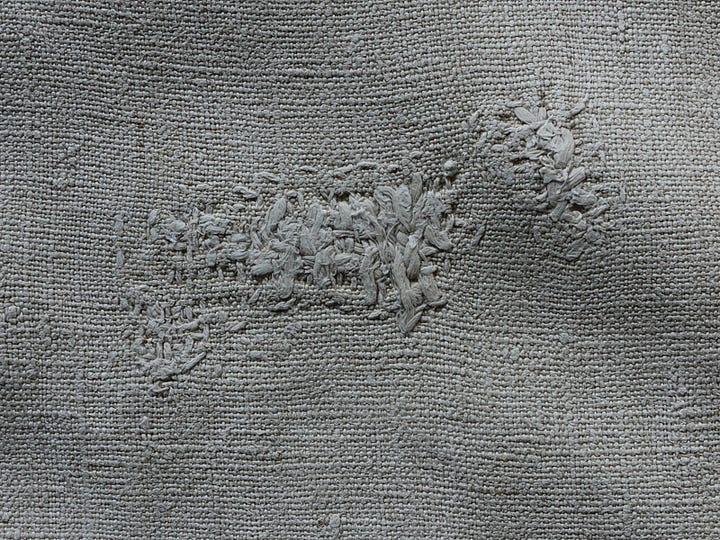

Here’s some photos of mending. Some of these pieces are in my collection, some of them were pieces that have since been sold, or will be sold, all of them are beautiful. And I hope they are inspirational, aspirational even. Taking care of cloth like this is something to aspire to.

I’ll start with the simplest things - shift chemises worn as underclothes and nightclothes by the not-very-well-to-do. These two examples show how making and mending don’t really have a clear demarcation. Both of these have been pieced together from different scraps, but whether this was how they were constructed, or how they were mended when worn, is not wholly apparent. It was probably a bit of both.

The next lot are grain sacks. In the region where I live, grain sacks were mostly made from handspun and handwoven hemp. The resulting textile was very precious, not just for the amount of work that went into the growing and processing, and then the spinning and weaving, for hemp might be a very easy plant to grow but it is a tough fibre transform into yarn, and it required great skill to be harvested, retted, stripped, spun, and woven in order to produce an outcome that wasn’t like a hair shirt. Although for a grain sack, hair shirt-like properties probably didn’t matter. The peasant also had to factor in sacrificing a field to growing hemp which could have instead grown food, or fed cattle, and for a short period of the year, the local river or stream would have been polluted with rotting hemp being retted, apparently the smell was incredible and it was considered an insult to do this near your neighbours.

Not incidentally, the incredible amount of physical labour and the very polluting methods needed to ret hemp (break apart the tough outer casing and render the inner fibre extractable and spinnable) are clear reasons why, when scaling up peasant fibre production for profit in the early 20th century, linen soared ahead and hemp was forgotten and discarded. Linen can be field-retted, a much gentler, less awful process which could be done on a much greater scale without rendering local water sources unusable. I will write more about this in my next newsletter. Have some grain sacks.

I particularly like the last two in this grain sack series, the patch on a patch of the very rough sack, and the simple cobble on an otherwise very fine herringbone-woven sack.

Next up is another utilitarian object, this one is a feather-stuffed mattress ticking bed cover. This will be for sale eventually, when I shake out all the feathers and soak and wash it. It is probably late 19th century, and it may have last been washed in the late 19th century. Don’t ask for the feathers, you really don’t want them!

This one again shows that there is no distinct demarcation between a make and a mend. Were these patches added afterwards or was the original mattress made out of lots of different pieces of fabric? In this case, I think it’s a little bit of both. Some of the fabrics used for patching probably predate the main body of the mattress. I love how precision and squareness has been sacrificed to the simple need for effectiveness. I doubt either the maker or the mender of this (who might have been the same person) had any notion at all that one day someone would find this utterly beautiful.

The next piece is a similar item but for someone a little wealthier. It is a cantonnière, a sort of quilted border which would have gone around the canopy of a bed at a time when canopies were’t romantic style notions but necessities in rooms where there might have at best been a fireplace for heating but very often nothing at all. This one has no mending to be seen, really, except that when you look at the back, you see that the original backing was indigo flamme textile, and that the tobacco-coloured fine cotton backing was a later addition. This might have also been part of the making - textiles were never wasted, and the indigo flamme may have always been enclosed like this because it was scrap being used as wadding. I thought to include it because it demonstrates the layering often used in old quilts, which were a form of extended practical mending as well. This also will be for sale soon on my website, when I do my next store update.

Incidentally, my website can be found here and I regularly update stock; an update will begin tomorrow.

Finally, this beautiful shirt is a ridiculously fine pure linen, dating I think from between 1890-1910 - I would put it squarely at 1900. Purchasing this was one of the only times I have been really cross at a seller in the brocante. This came out of a huge haul of linen and cotton clothing, several beautiful trunks full. The labels on the men’s shirts were bespoke tailors from Poitiers and Angoulême, all the pieces and the trunks themselves spoke of a very wealthy household. But they were rotting and the trunks were ruined beyond repair. ‘Oh’, said the seller, ‘yeah that’ll be because I dumped them in the barn where the roof leaks’. He’d evidently cleared out an entire wealthy house some time back. The pieces he deemed worthy of attention, he’d long since sold. Now he was just squeezing the last drops from the haul. The irony is, if the quality of those pieces of clothing was anything to go by, in a good state they would have been rarer than most furniture, and worth more too.

I held my tongue and bought several pieces just because even in their ruined, rotten state they were amazing, and because I just felt I had to save them, for what I don’t know. But they rewarded me; when I got this one home I noticed all these tiny repairs - another women’s shirt, so very fragile, showed the most incredible fine pleating I’ve ever seen on any garment. And the men’s shirts, which survived being washed but are completely unwearable, have gone into my small collection of clothes I keep to make patterns from, such was the beauty of their structure. Even ruins teach us something.

Clearly someone loved this shirt very very much. There’s something very deep and very important in that, and in the gesture of mending it. Visible care.

I like the notion of things accumulating soul over time. It describes how I feel about my old house, and all my old tools, looms and wheels especially.

Oh my. The ticking, and the shirt. Sometimes I feel like I may be quite mad feeling the way I do about these things - knowing that you do too always makes me feel in good company. Thank you for sharing, Johanna. ❤️