The King of France versus India

The precursor to the present day drama "The King of America versus China"

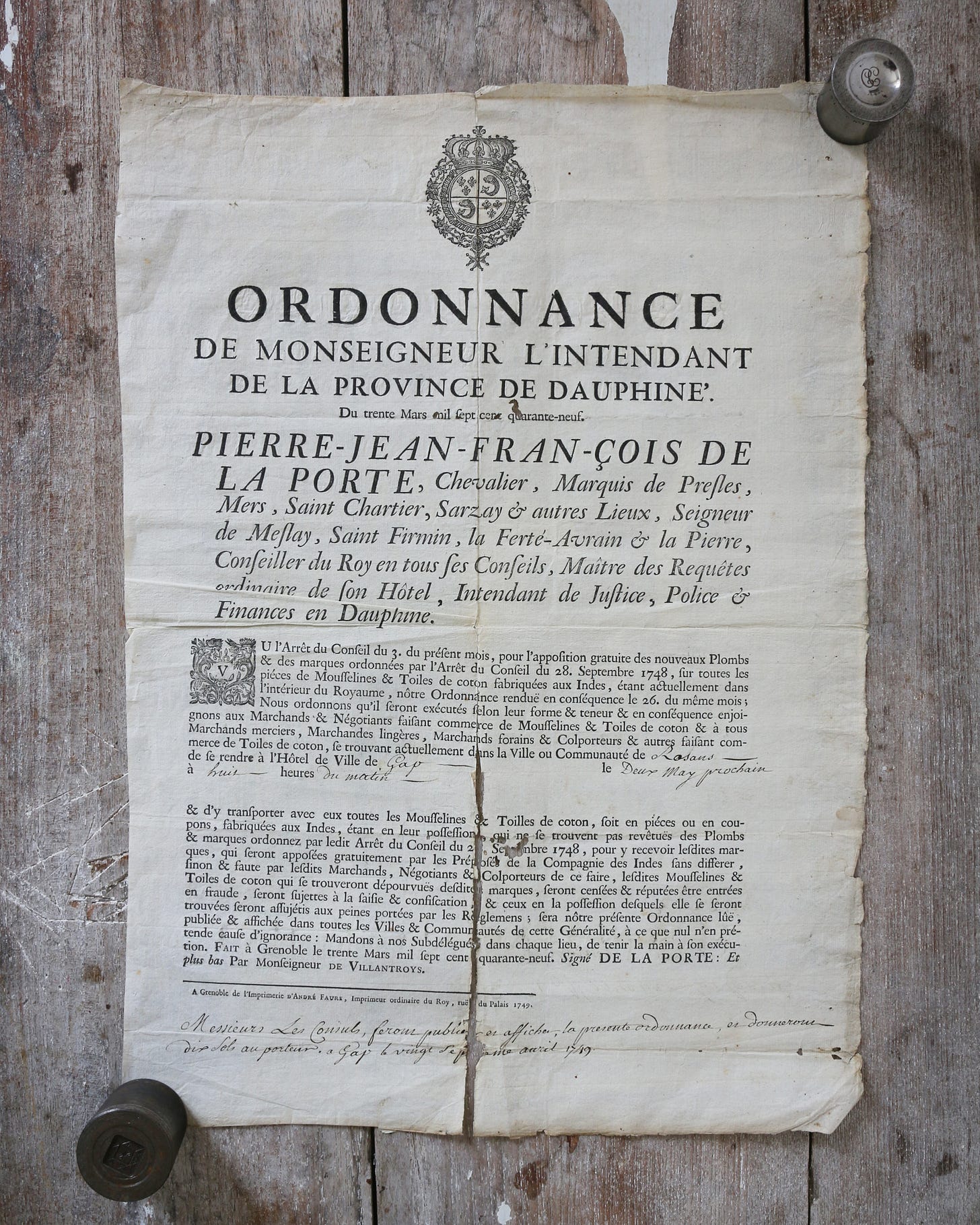

This piece of paper is very large, a little bit damaged, and rather old.

Dating from the 30th of March 1749, this is a royal ordinance from the region around Grenoble, just south of Lyon, a region which has historically been one of the great centres of textile production in a country which was itself one of the great centres of textile production and dissemination .

This document has been printed under the auspices of one Pierre-Jean-Françoise (or Fran-çoise as is written here) de La Porte, otherwise knowns as a Knight, also the Dauphine of Presles, Mers, Saint-Chartier, Sarzay and various other places, otherwise known as the Lord of Meslay, Saint-Firmin, La Ferte-Avrain and La Pierre, otherwise known as the King's counsellor in all things he needs counselling in, otherwise known as the Master of Requests - an honorary title which was extremely prestigious and which he actually would have paid a whopping sum of money to hold, which essentially afforded him to be the head of the local judiciary and also to hang out with the King if and when the King ever showed up to what was a fairly distant province on the border with Italy...but wait, he was also otherwise known as the Royal Agent for Justice, Police and Finances in this province, formerly called Dauphine.

In other words, Pierre-Jean-Fran-çoise de la Porte was an extremely wealthy and extremely powerful regional ruler-by-birthright whose only superiors would have been senior courtiers in the King's entourage, and the King himself. Other than being born to his power and having a King as a superior, de la Porte sounds very much like a few people we know today, who like to invent titles and then bestow them on themselves, often purchasing the right to do so with extraordinary amounts of money, so that they can then grant themselves the right to make even more extraordinary amounts of money by changing laws and imposing taxes to suit themselves and their handlers.

And this piece of paper is exactly that, a way of making money. In the first paragraph it states that new 'plombs' had been approved the year before. A plomb here is referring to an actual small piece of stamped lead, hence the word ‘plomb’, that was affixed to pieces of fabric (and maybe other things but I only know about the fabric part). Right up until the mid-20th century, some fabrics still carried these stamps. I have found rolls of relatively recent cloth still bearing a plomb, and yes, they were lead. These plombs would have indicated that the merchandise had been inspected and complied with duty and taxes, as well as with laws pertaining to what was allowed to be sold. In later years they might have also indicated the merchant's seal, but at the time we are looking at, these were royal seals, under the auspices of the King.

This document is stating that there are recently-approved supplementary stamps which need to be affixed to all cotton toiles (that is, cotton fabric), to complement the stamps they should already have had affixed, and that all merchants and dealers and middlemen and transporters, market-sellers and door-to-door salesman (colporteurs) need to rock up to the Hotel de Ville on the 2nd of May at 8am in the morning to obtain the necessary new stamps.

So far so good, although those of you with any knowledge of textile history in Europe might have picked out something already.

This something is made clear in the second paragraph, when 'Mouffelines et toiles de cotton fabriquées aux Indes’ are singled out.

In fact, all cotton that was coming into France at this time was made in India, and so this whole documented is a cleverly-worded mandate for taxes solely and specifically on imported Indian textiles.

In short, this is an application of tariffs.

There is no mention of wool, or linen, or hemp, the three indigenous French fibres. There is no mention of silk, which, though not an indigenous French fibre had long been raised, transformed, and woven in France, and was a particular speciality of Lyon, the largest city in this region. No, this is targeting imported luxury fabrics, because these imports, around this date of 1749, are beginning to make a real and damaging dent in local fabric production and sales.

Indian cotton had no rival in France, or in wider Europe. When it first arrived in Europe, it caused a sensation which didn't die down for hundreds of years, not until...but we will get to that later. France already had in the ports of Nantes, Bordeaux and Marseille some of the biggest trade-ways Europe had yet seen, although Italy, and Holland especially, were rivals. French merchants were well-known for their textile trades, crossing regularly to England for woollen cloth, to Italy for silks, and to Holland and the north of France for linen. France's geographical situation, relatively mild temperate climate, and huge political and military clout saw her being the crossroads of everything obtainable throughout Europe. French artisans were also remarkably skilled - from the very beginning they exploited all of the above, taking on new materials and technologies and techniques and refining and perfecting them. France was one of the great global centres of not just textile production, but textile knowledge, even before the beginning of European colonisation.

But with the beginning of trade with India, and then colonisation of India, textiles unimaginable to the western senses began to enter Europe, first in a trickle, and then in a flood. Cotton, when it first came in, must have been an absolute marvel. Indian cotton was soft and warm and floaty and fine; spun and woven by hand, it had already had thousands of years of savoir-faire and refinement behind it by the time Europeans first came upon it. The finest cotton ever known on the planet came from Bengal (and is now extinct, thanks to the British East India company. Don't believe me? Read about it here). Textiles of surpassing beauty began to appear in the market. Apart from being made from that wonder-fibre, cotton, Indian fabrics had one other remarkable feature that could not be found in Europe. They were printed.

Ok, here I am going out on a limb which hasn't yet broken beneath me but may still. My knowledge of natural dyes, dyeing techniques and fibres, plus decades of looking and thinking has led me to conclude that there was no local way of patterning cloth reliably or in large quantities using printing in Europe prior to the introduction of Indian textiles. If someone would like to provide proof of indigenous European cloth patterned by printing techniques that were not lifted from Indian and South-East Asian textiles prior to the 15th century please do bring them to my attention. But every single example of indigenous European textile I have seen prior to the introduction of Asian fabrics beginning in the 17th century as a trickle and becoming a huge flood by the 19th century shows that patterning was done in a variety of ways, but not by printing. European textiles were patterned by knitting or weaving the design in using threads of contrasting colours - they were created using tapestry techniques - again in single-colour threads, or they were embroidered or laceworked in.

Meanwhile, over in India, weaving and embroidering patterns had reached an extraordinary pinnacle hundreds, if not thousands of years before Europeans ever encountered a single Indian thread. Go search and study Jamdani fabric, a very ancient textile which is still produced today, just as a taster of what Indian weavers were up to.

But Indian textile artisans had other techniques up their capacious and extremely beautiful sleeves. They were producing amazingly detailed painted and printed textiles using a variety of natural pigments, chemicals, and extraordinarily sophisticated printing techniques. Block printing, hand painting, resist printing and wash-out printing, in which a textile is printed with a colour and then some of that colour is removed using chemicals whilst other colours are applied, were all long-established Indian techniques of adding pattern to textiles. India's diverse climate and well-established interior trade routes meant that her artisans had access to an incredible palette of natural dyes plus the specific technologies that went with each dye and its chemical makeup. And India was also the centre of some of the oldest and most extensive global trade-routes the world has ever seen. Indian merchants traded for millennia throughout Asia, China and the Middle East, and the dyestuffs they must have had access to from China, from Persia, from tropical SE Asia, from Turkey, would have been astonishing. All of this meant that by the time Europeans stumbled belatedly onto the scene, Indian textile artisans were producing textiles and garments of such fineness and delicacy, with such bright colours and intricate patterns, that when they first entered the European market, people lost their everloving minds.

(For a taster of the sorts of things that began to show up in the European market, go look at the Instagram feed of collector, scholar and writer Karun Thakar - starting with this post).

So our ordinance here dates from the time when these amazing textiles were just beginning to enter the European general market. The nobility of Europe had had access for a while already to these textiles, but by now they were beginning to be available in such quantities that lesser nobles and the bourgeoisie were beginning to be able to get at them. This must have made not a few royal personages quite miffed, because there were already laws about who could wear what. Silks, for example, were not to be worn by the lower classes, should they even somehow find the means to afford them. Even if your rich connected relative decided to give you his fifth-best silk cloak, bad luck to you if you were caught wearing it in public.

But the King and his underlings, of which de la Porte was one, were also annoyed because...

Because these beautiful textiles that were coming in in a flood had no agreed-upon price-point; because they were undercutting local weavers and dyers, and because none of the revenue from their import or sale was coming into Royal coffers.

And here, once again I must make mention of indigo, because of all the things that pissed the government off the most (and not just the French government, also the English and German governments of the day) it was the fact that Indian indigo was simply marvellous compared with the local product, woad.

There are hundreds of different plants all over the world which bear indigo pigment. Woad is one of them. But woad has a very low pigment quantity, and a great deal is required to make darker blue shades (and here I must also add that there are several modern French organisations which claim to only use woad and are producing very dark colours and I have it on excellent authority that it is because they add Indian indigo to their vats...so there). By contrast, the species of plant from which Indian indigo is obtained (and which gives the dye its English name from its botanical name Indigofera), is extremely high in blue pigment and that pigment is so accessible that with a relatively crude fermentation, you can easily get at it and make it into measurable cakes of pigment which can then be transported and used easily.

So the cotton fabric itself was already pretty bad news for local growers, spinners and weavers, who simply couldn't compete at that price-point with Indian cotton and couldn't compete at all with any cotton full-stop, as cotton is not indigenous to Europe and won't grow here. The warmth and fineness and softness of Indian muslin cannot be replicated with linen, they are two radically different fibres with very different qualities. Once again here I will take the time to remind the reader that cotton is a beautiful and sacred fabric with exceptional qualities that no other fabric possesses, and that it is only Western exploitation of cotton and the links that that exploitation has with slavery and mass-production that has made the modern consumer think of it as a lesser fabric than linen.

And nobody could compete with those beautiful patternings, not the bright vibrant colours, nor the intricacy of design. European dyers lacked the necessary dye-plants and techniques to compete with thousands of years of Indian savoir-faire, and they rapidly began to feel the heat. The woad dyers felt it first, and the entire industry - and it was up until this point a very big industry, employing a great many people and producing a great deal of cloth and a lot of revenue, quite a bit of which ended up in Royal coffers - began to go under. Although it isn’t stating it, this mandate here is targeting not just Indian cotton but indigo - other mandates in England and Germany and France from this same era specifically mention the banning of the import and sale of Indian indigo-dyed cloth, in a desperate but futile attempt to protect the local industries and their workers. And their taxes.

So this is why these merchants and dealers were being asked to bring their Mouffelines to the Hotel de Ville on May 2nd. To acquiesce to a new tariff, a tariff imposed for all the usual reasons - to protect local industry, but to also allow those in power to have a slice of a cake that had been hitherto out of their reach. If the merchants and door-to-door salesmen of 1749 failed to comply with this Royal decree, their Mouffelines would be seized (and no doubt de la Porte, after fending off his wife and daughters, would have made a big fat profit by selling the seized goods over the border in another département. There are different laws for rich people, as us peasants have always known!

But here comes the lesson. The bit that the self-proclaimed King of America, the smartest man ever to hold office, a man so clever that they are all saying he is a genius, hasn’t quite managed to grasp, although it is rather basic.

Actually there are two parts to this lesson.

The first is that, despite what the King of America is telling his loyal subjects, tariff costs get passed on to the end-consumer. In the case of these Indian cottons, the end-consumers were not the huddled masses of peasants. No, they were the minor nobles and the emerging bourgeoisie, the wealthy middle class. They were people who could quite likely do a bit of weight-throwing of their own, if they got annoyed enough. Lesson number one: Beware who you piss off. And remember that though the French Revolution was started by peasant grumblings, it was finished off by an elite class of the bourgeoisie, aided and abetted by quite a few contemporary nobles, all of whom saw ways to benefit from a state whose king and queen had lost their heads and where chaos ruled, and Indian and other trade routes existed and were open to all who had the money and the power to control them.

The second is that, if you are going to impose tariffs on a country, make sure your own country has the ability to produce en masse and with enough skill and finesse the goods that you are trying to prevent entering.

Because, as discussed above, no European technique or fabric could rival anything, anything, ANYTHING, that India had to offer.

You can imagine the discussion. "Manon, put down that beautiful incredibly fine cotton dress with the shocking red and blue and green and yellow printed flowers and birds with a matching shawl that you can pass through a wedding ring and that is so light and airy to wear in summer that it feels like you are wearing nothing, because it costs more than Papa's second manor house and we are only buying French, so shift your bodice over here and try on this scratchy grey felt jacket, or what about this lovely linen-coloured linen with brown stripes, or what about this exquisite exorbitantly priced silk...oops sorry you are the daughter of a wealthy merchant but we alas are not of noble blood; that silk cannot be for you so let's go back and peruse the grey felt jacket again.”

(Listen, European cloth and clothing makers were capable of making incredible things too, I am exaggerating a little here, maybe, not much).

Manon would have rebelled and gone and cried on Papa's waistcoat (not silk, but quite possibly Indian cotton). Papa's eyes would have smarted with the injustice of it all, and his calculating brain would have seen opportunities afield if only those obstacles (the King and his bloated entourage) that forbade him from going on a free-for-all rampage across the known world would just get out of the way….

We know what happened, because... honestly, if I write how we know they did this short newsletter will turn into a book.

So, shorthand, we know they did, because colonisation. India was first and foremost colonised for her textiles, and for access to indigo, just as the transatlantic slave-trade was primarily about indigo to begin with. Underestimate textiles and their importance in history at your peril - textiles ARE the main character.

Gold and spices are all very well and good and rich people loved them, for sure. But when you have something you can sell to rich people PLUS variations you can sell to the masses, well, now you are onto something good. There are no cut-price diamonds, but there is second quality cotton and cheap mass-produced indigo cloth. Made even cheaper when it is grown on someone else's land using someone else's forced labour and resources. No wonder European merchants were laughing all the way to their many banks, which had first sprung up around the 14th century to uncoincidentally coincide with the invasion by Spanish conquistadores into the New World and their subsequent ransacking of huge amounts of gold, all of which needed a place to be stored. And with banking sprung up that other hydra head - insurance. The modern world began to be shaped.

Meanwhile France's love affair with cotton rapidly turned vicious. Finding that the British had largely beaten her in violently annexing India and her textiles and her indigo, France diversified. First she stole a lot of the techniques used to make those beautiful printed fabrics, brought them back to French soil, adapted their methods for local uses and tastes, and began churning out her own local versions of these textiles, called, to this day 'Indiennes'.

An example of a French domestic Indiennes textile from the mid-19th century - this is part of a complete cantonnière which is available on my website at the moment - you can go and see other photos there. This is backed with indigo flamme fabric - another style of patterning which had its origins in Asia, Africa and South America.

But not content with this tiny slice of the pie, France decided to follow Portugal into Africa, where she discovered there was lots and lots of cotton and also lots and lots of Africans who knew lots about both cotton and indigo and didn't know very much about the utter evil of European colonisation, and so France took over the small existing transatlantic slave trade started by Portugal and massively expanded it. In time it became a joint venture between France and the UK. This opened up those previously barren except for lots of trees Caribbean islands full of useless natives and annoying pirates, and both France and England rapidly installed themselves there with overseers and enslaved Africans to grow indigo, and then sugar, and then other things, and from there it was a hop skip and a jump over to the New World and the whole violent sorry mess which is currently reaching its apogee under the Orange Thug the King of America.

It is not at all coincidental that chattel slavery reached its peak at the same time that France began consuming cotton and indigo textiles in huge quantities, and not just for the upper classes but largely en masse for working people, and for the army and navy. Unable to come to agreements with the British about who could steal what from India, France is hugely responsible not just for the transatlantic slave trade but for the whole system of slavery and its governance within North America. France was one of the largest customer for all that New World cotton, some of it indigo-dyed. Hell, France, in the form of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the founder of the Gobelins Tapestry Workshops in Paris, a man whose name appears in numerous French streets and ways, (and who was also instrumental in the runnings of the French East India Company) wrote the handbook on the treatment of enslaved Africans - a book which eventually became a huge part of the law of the New Colonies and which is really the legal basis of the modern United States. The US likes to proudly cite the Declaration of Independence as its founding doctrine, but I think Colbert's Le Code Noir is the true ideological basis of America.

There's another lesson here. The West, unable to share, barter or pay for the goods it wants and depends on, has historically instead stolen, invaded, annexed, killed and enslaved to get its hands on other peoples' stuff. We can see this clearly in the colonisation of Asia, Africa and the Americas. But we can see exactly the same behaviour in the late 19th and 20th centuries in the Middle East and North Africa. And we are seeing it violently and graphically right now playing out in Palestine and Congo and Sudan. Yesterday it was Mouffelines, today it is coltan and petroleum. The West's obsession with all things which are not ours by birthright, coupled with a centuries-old state- and Church-endorsed belief in white supremacy that runs so deep most of us can't even begin to fathom how it informs our worldviews and our own day-today lives; these two things have irrevocably shaped the entire world and the lives of all its citizens. Climate change is an outcome of this, as is endless war. The time of reckoning is here now, what has been taken must be paid for, and all I can say to those of us who know what is upon us is: keep quiet and plant trees and heaven help us atone for our sins and those of our ancestors.

(And to all those people who come into my DM's and tell me why don't you shut up about politics and stick to textiles, to those people I would like to say kindly remove your two brain cells from my space and go back to your log in the swamp :D)

Did you like this newsletter (free). It takes me many many hours of thinking and writing to put newsletters like this together. Perhaps you may like to share it, because sometimes people read my newsletter and then they go to my shop and they buy a textile or two, and that is what keeps my little family and my dog Hugo fed and watered.

But also, perhaps you'd like to enter my next round of...RAFFLES!! With EXCELLENT TEXTILE PRIZES!!!

It has been a while since I have held a raffle and I am sorry about this, because I do like to keep doing things that I have started doing. I have been not 100% well these past months and these raffles take quite a bit of time to organise and run. But we have done such a wonderful job over the past year, so let's keep going.

I have two raffles today. The first is for a young man I have been fundraising for since early last year. His name is Abdalla and he is a nursing student in Gaza. I have written quite a bit about him and his situation in previous newsletters. I randomly picked him and his family from a list on the Operation Olive Branch profile, so he has been vetted and is a real genuine person, the same age as my daughter. He has lost everything, his home, his school, his future, and this raffle is to provide as much money as we can to help him keep his family fed. Food prices has skyrocketed in Gaza, as Israel has now blockaded all aid, foodstuffs and water not to mention medical supplies since early March. I was originally fundraising to his GoFundMe, but GoFundMe is not going to let him access funds until the target is reached, and in the meantime he and his family are in dire need. So, despite my hatred of Paypal, Paypal it is, because Paypal is the only way money can be transferred directly to him. even with high fees. The Paypal account he is using is not in his name, because Palestinians are not allowed to hold Paypal accounts - the owner of the account is transferring the money to a local bank. The fees incurred are high - we must just consider them as part of the cost - this is what happens in parts of the world which are being destroyed by the evil outlined in today's newsletter. I have already run several raffles asking people to donate to this Paypal account and can confirm that the money is reaching him and is helping enormously

So:

Raffle Number One is for this vintage resist-dyed Dutch kerchief. These kerchiefs are a very old tradition which (yes) has its technical and stylistic basis in India, via Indonesia, via Dutch colonisation. In turn these working man's kerchiefs were the design inspiration for the rockabilly bandannas of the 1950's and beyond into the 60's and 70's. They are a design and fashion icon.

Originally they would also have been indigo-dyed. This one is not, past the late-19th century most natural indigo was replaced by synthetic indigo, but it is still beautiful. This one probably dates to the 1930's or 40’s. It is in excellent condition and measures 89cm square.

To enter, please send €10 (or more if you can to this paypal account) : @akam0503

If it is easier you can use this link to get to that account : https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/akam0503

Take a screenshot of your donation, and send the screenshot to lagrossetoile.deux@gmail.com.

Please use this email which I set up specially for these raffles because if you use my usual email, your message might get lost.

Raffle number two will be for Palestinian Action in the UK. I don't know about you but over the past 18 months I have moved through disbelief and horror, past grief and sadness and shock, and am now in my incandescent rage phase. I am so angry I want to break things, namely most of our leader's skulls, but also weapons factories and their CEO's. Whilst the US is the principal driver, funder and armer of both the white supremacist colony of Israel and of the genocide, good old Blighty is also supplying not just weapons but intelligence to the IDF using British airforce reconnaissance information. This genocide is the usual European American joint effort.

Palestinian Action are a radical group of people who break stuff. So far they have managed to successfully and permanently close three of Elbit's weapons factories in the UK. Their members risk absolutely everything to do what they do, often ending up in jail, and the least we can do is send them some bail money. Particularly if we can't throw bricks ourselves. You can read more about them on their Instagram page here or their website.

Raffle Number Two is for these three skeins of antique French and Belgian linen lacemaking thread. I have deliberately chosen three contrasting skeins. The thickest is 20 metres long, but the largest one is at least 40 metres long . The fine ones are wonderful for stitch-work.

To enter, please send €7 (or more if you can) to this link here

Take a screenshot of your donation, and send the screenshot to lagrossetoile.deux@gmail.com.

Please use this email which I set up specially for these raffles because if you use my usual email, your message might get lost.

I will pay postage tracked but uninsured to anywhere in the world for both these prizes. If you would like to pay for postage, I will ask you to donate the cost to the relevant raffle and I will post them anyway. If you want insured postage we can discuss a top-up.

As always, thank you for following me this far :)

xx Hanna

Thank you Hanna, for this great foray into history. You have informed me so much since I started following you, it has changed my views so much on European colonisation, and all the things around this. I’m sure my friends and acquaintances are sick of me quoting you, but I’m hoping to inform people like you have inspired me! Thank you!

Wonderful as always!

Just because:

I'm fairly sure I've seen stenciled silk that predates the introduction of Indian printed cotton, but it's nothing like the amazing detail of the printed cotton. They appeared to be imitating damask, so it never would be as detailed. Silk accepts dye fairly readily, but linen has, until recently, been hard to dye in a strong colour, let alone print on it. I'm not sure how the process has changed, but 30-40 years ago you just didn't get the strong colours in linen that you get now, and anything printed barely penetrated the fabric. It's hard to imagine a world with largely unpatterned fabric!

Australia also has a plant that produces indigo - indigofera australis(?) - but I've never seen anyone get a decent amount of colour from it. I think it's related to wattle, from memory.

And, lastly, please keep being political!