I've now been looking closely at antique French sheets for over 6 years. Who would have thought! I started by knowing so little, and whilst I still have lots of questions I want answered, I do know a bit more now than when I first started.

Right from the beginning I came at a slightly odd angle. I see lots of people obsessed with the intricately-embroidered 19th century linen sheets, and they are indeed amazing and becoming very rare. But this business started because I met French antique hemp, and, having never encountered such a beautiful textile personnage before, I fell deeply in love.

Hemp is a peasant textile. It was rarely embroidered, rarely embellished at all. It was hardwearing, serviceable. I doubt that many people 150 years ago would have thought it was particularly beautiful - it was just there, it did the job.

But to me, looking on with young eyes centuries later, from the privileged position of not having to grow, process or weave it, hemp was lush. I started collecting pieces of hemp, hemp sheets, hemp tablecloths, hemp tea-towels. I didn't know then but I do now; I had inadvertently landed right in the heart of one of France's richest textile regions, an area which had centuries of knowledge of hemp growing and processing, but also, at the other end of the social scale, was home to some of the richest estates and châteaux in the whole of France, with their accompanying textile wealth.

I was also lucky enough early on to come across two sellers in my local brocante who were as obsessed with hemp as I was, sellers who don't deal in fancy stuff but specialise in going into the deep country and clearing out old farmhouses and peasant estates. It took a while but they began to teach me what they knew, and to set things aside for me. I've now known them both for almost as long as I have been running this business, and they are the source of much of my knowledge and quite a lot of my stock.

I now have a collection of around forty hemp sheets and many other pieces besides. Each piece is different from the last. Each shows the variations of the conditions the fibre was grown under. Each exhibits the maker's hand. Some even have a little embroidery, a peasant girl trying to make her life just a little bit more beautiful perhaps. Hemp, and peasant textiles in general, taught me to look carefully at textile pieces, to see the work involved, even when that work is not flashy, spectacular, or made of intricate printed or embroidered designs.

And so I come to ladder borders. I actually have fewer linen sheets than I do hemp. This is because in general I keep the hemp ones because they exhibit certain qualities, but the linen sheets I sleep on, and however much I love them, I don’t need forty of them! But I don’t go for the embroidery, I go for the quality of the linen. I don't care so much about the embroidery - indeed most of the embroidered sheets I find, I sell, although I have kept a few that I particularly love, a design of holly leaves, another of raised oak leaves, and a spectacular but damaged example of Touraine embroidery with recognisable flower and leaf motifs spring to mind. Most of my own collection of linen sheets are plain, with ladder borders. But all those ladder borders are made by hand, and the amount of work involved is insane.

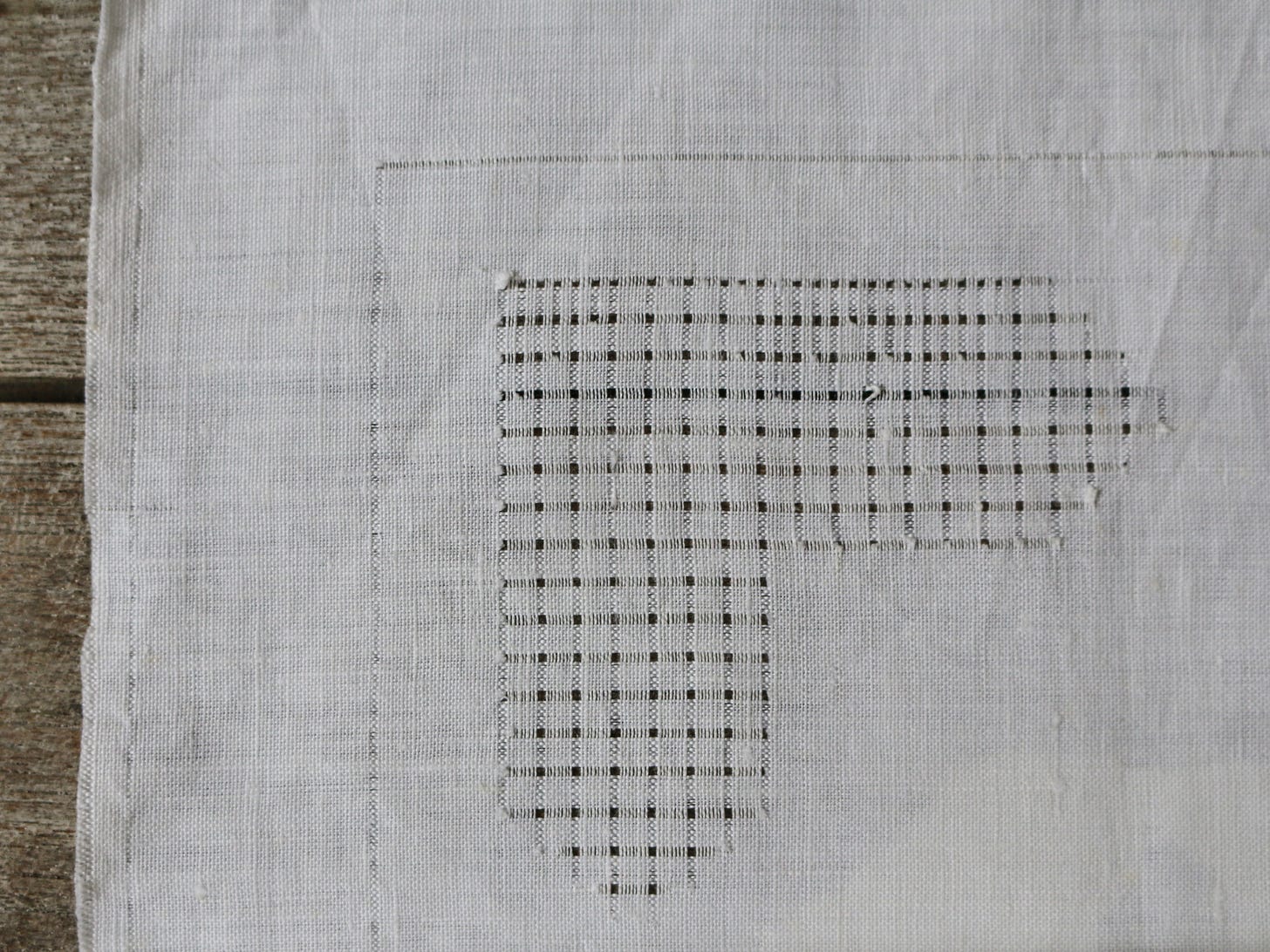

Ladder border on a fine piece of linen, c. 1910

The easiest way to explain how they are made is to direct you to several videos. They are both in French, but it doesn't matter if you don't understand. Just watch. The first shows the marking out of the ladders, but not the wrapping. The second shows the wrapping, but it is not as well-filmed as the first - I've included both because I think the first one shows you how fine the work must be, whilst the second expands and shows you the second part of the work in making the 'rungs'.

Bear in mind also, that even before either woman in these videos gets to the point of making the 'rungs' of the ladder, they have already pulled out all the warp threads in the textile. Now, you cannot just get one end of a thread in a piece of fine linen and pull it and expect it to come out cleanly. You might have some success with most modern linen, which is comparatively flimsy and loosely-woven, but with vintage and antique French linen, nope, not a chance. No, using a needle, you will need to pick out the thread from the weave every two to three cross-threads, to loosen it. I have tried to do this with linen from around 1930. It made me cry and took me over an hour to get a single thread loose across a metre or so of textile. Now imagine how many threads you have to take out just to get the width of a ladder border, And remember that you must pull these threads out gently because you need the cross-threads to stay intact and strong (ie. if you are pulling out the weft threads, you need to make sure you don't damage the warp threads. Usually it is the weft threads which are removed for the longest part of the border, but down the sides of a sheet or for more intricate patterns, the warp threads need to be taken out as well). I have watched a professional with decades of experience, it is still painstaking work that takes hours for metres of fabric. I have examples on exceptionally fine linen as well, pulling threads from handkerchief weight linen must be extraordinarily difficult.

(It is also the only way to get an exact edge on a piece of linen, antique or otherwise. Pull out one complete thread and then cut along the fine gap that is left.)

Ok here is the first video.

And here is the second.

So that’s ladder borders. Now it gets fancy.

Last year, one of the sellers in a brocante I regularly attend decided that he'd taken a shine to me and told me that he had a load of stuff coming in that I might be interested in. Usually when this happens it ends up being a collection of 1960's bri-nylon dresses, or 16 cartons of harsh post-war linen mètis sheets of dubious quality. But this time it was the entire atelier of a woman who was an embroidery artisan, working in the 50's and 60's. She died last year or the year before - she must have been in her 90's, and here was the contents of her atelier. I swooped, and bought the lot, boxes of linens, rolls of unused linens, and various sundry things that were at the bottom of boxes. If you bought a very good quality new-old sheet off me last year, one with a ladder border, chances are it came from this woman.

But amongst the finished pieces I subsequently sold were other things, just as precious. Pieces that were in various stages of progress, a snapshot of her work, as though she had just laid it down and gone out for a coffee. Here are some of those pieces - showing various steps in making a drawn-thread border or design.

The first image shows the textile with the threads drawn out, in the second photo the threads have been grouped into bunches of four, secured with tiny stitches, and then they have been wrapped and woven together to form the design.

This woman was a specialist in all sorts of drawn-thread work, including a type of intensely geometric drawn-thread work called 'jours d'angles'.

At first I thought that this name referred to the geometry of the designs. I don't know the origin of the word 'jour' here, it certainly doesn't translate as 'day', but, for example, in the videos above, the first one shows the making of 'jours d'echelles' - ladder borders, and the second one is 'jours de venise' - wrapped borders (Venetian borders, apparently named because this was a style much used in Venice in the 15th century). So 'Jours d'angles' I thought might be angular borders. But actually it's named after a tiny and exquisite town called Angles-sur-l'Anglin, in the modern-day department of Vienne, not too far from where I live, and three minutes drive from a house I am currently trying to buy (for anyone interested in following my house-acquisition progress, my paid newsletter is full of the trials and tribulations!). So it's more rightly called, Jours d'Angles!

These two images show the beginning of Jours d’Angles work, and the precision with which the threads must be drawn out in order for the finished work to be perfect.

Amongst the boxes of textiles was one extraordinary folder full of explanatory step-by-step notes about the making of Jours d'Angles pieces, complete with samples and photos. Here are some of those notes and samples. There were also some very beautiful gelatin black and white photos, I would love to show them to you but photos of photos are not great!

Step one - the translation says ‘Pulling the threads - Stage one

I count and pull up the weft threads in the textile to determine the number needed to position the motif’

You can see at the bottom the looped threads that she has pulled up but hasn’t removed.

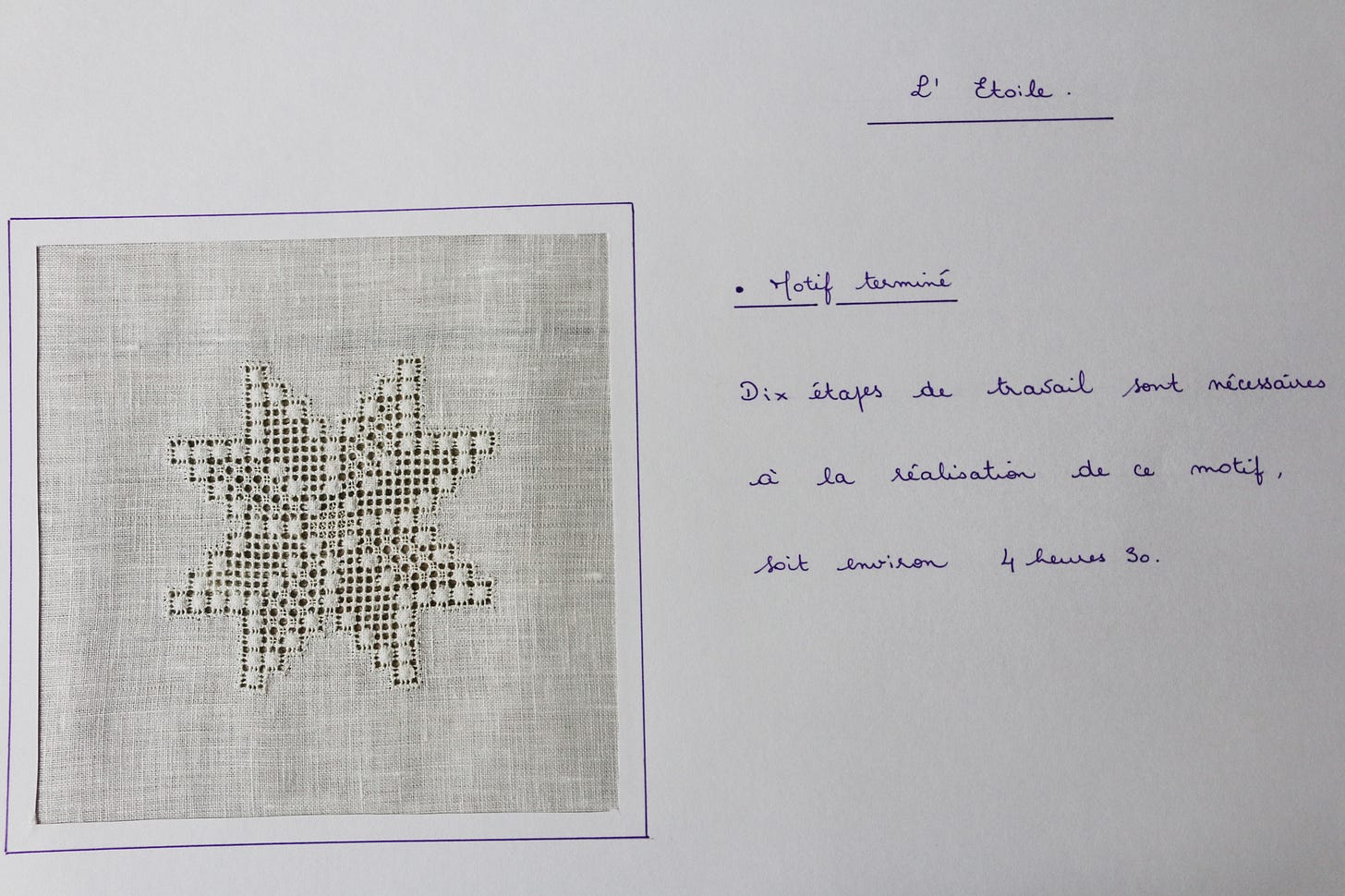

These pictures show some of the stages of making this star design. The last is the finished product.

This is the same picture as above but with its note which reads:

“Finished motif. Ten steps of work are necessary to complete this motif, which takes around 4 1/2 hours [for an expert artisan with many years experience].’

The star is around 6.5cm high. I have sold tablecloths that were four metres long and two metres wide, with entire thick borders of this work. Imagine the time involved.

I haven't much else to say. I think the videos and the photos do it all. Are you surprised by the amount of work that goes into such a simple decoration as a ladder border? I must admit that I am not surprised by anything any more. The amount of work that goes into the least of these textiles is phenomenal, as is the skill level. I am struck especially by the handwoven linen and hemp mens workshirts, of which I have handled hundreds by now. Every single one perfectly made. But it wasn't until two years ago, when I took a shirt-making workshop online with wonderful Sarah @sewnstories and realised that they took hours and hours and hours and required utmost precision and perfection. And then when I began to look at them again in the new light of having tried to make one, I saw that every single shirt that crosses my path exhibits a degree of skill that I would cry to have, even the least of them is acres better than I can do, and the best of them, if you look carefully at the seams and stitching and pleating, is next-level amazing, even though the end result is a seemingly-plain piece of 19th century workwear.

At some point I have just had to believe that most of the pieces I handle contain days, weeks, and months of work. This is what we used to just do, without it being something we were known for, these were just skills we were expected to know and exercise.

By the way, I recently went to Angles-sur-l'Anglin. It's a gorgeous little village full of very picturesque buildings dating from the 12th to the 19th century. It has a ruined castle perched on an escarpment overlooking the Anglin (any town that is called -sur-something means it is next to a river or stream). It has an Association for the Safeguarding and Dissemination of Jours d'Angles (an attempt at a direct translation!) but when I mentioned to the owner of the restaurant opposite the closed office of this Association, that I had documents I thought should be given to them, she told me that the Association had disbanded, there was so little interest.

Jours d'Angles are passing into memory now, except for hobby embroiders. Just one example in many, many, many…

I hope this helps you to see the work in the details!

so lovely to wake up to the wonderful threads of linen .. literally lying in bed reading this. I am a linen fan and have my own stash in my French atelier.. it is mesmerising and so comforting to capture a glimpse of the value of times gone by .. merci!

I'm slowly reading the newsletter that I hadn't time to read before, so my comment arrives a bit late. In this you speak about "jour d'Angle", with "jour" clearly not meaning "day". I would imagine someone told you by now, but just in case (as french is my main language): a "jour" is also a small hole (not necessarily in a textile or made purposefully), because through a small hole you can see light, and of course day light. I hope this is interesting to someone. It's amazing to imagine the work that went in each piece of textile with all that manual labor. Thanks for sharing and showing us!