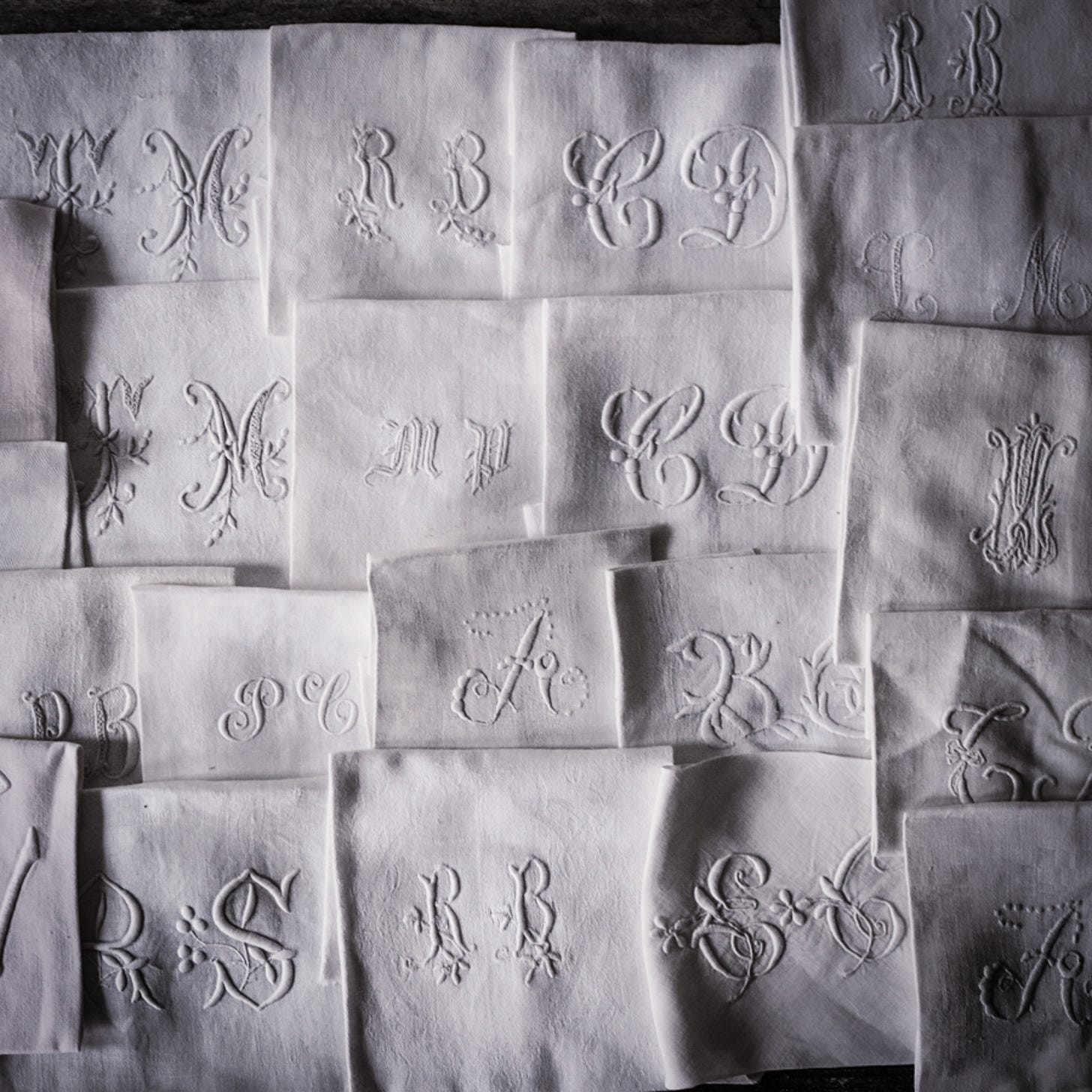

Many if not most of the household linens I find have initials embroidered or cross-stitched somewhere, be it in one corner, or the middle, or both sides. The method, placement and decoration of these initials tells you a great deal about both the owners and the original usage of the piece. The more intricate and delicate initials or monogrammes were, the more centrally-placed, the wealthier the original owner was. These types of initials, or more often monogrammes, carefully-designed patterns which incorporated the owner's or family's initials, were made purely to designate ownership and show off wealth. These pieces were valuable and expensive even in their own time, and until well into the 20th century, they were included in summaries of the wealth of an estate, and formed part of inheritances. In the early part of Suite Francaise, written by Irene Nemirovsky, herself a French Jewish writer who was deported and died in Auschwitz in 1942, there is a description of a bourgeoise family fleeing Paris as the Nazis move in, and during the frenzy to pack the car and get everything valuable under cover, Madame Pericande remembers that the most valuable of the household linen has been left with the laundry, and instructs her maid to go and fetch it. The still-damp linen is bundled into the car as the family flee the city in search of refuge.

My last house was leased from the large manor house across the road. The manor house, referred to in the small village I used to live in as the Château, was built between the 17th and 19th centuries, and its huge park contains the village church, an orangerie, a 15th century house, and numerous huge caves. It stands on the site where a much older château, one dating from the 12th century, with white stone and turrets, stood until it burnt down in the late 18th century, an incident which I was told had nothing whatsoever to do with the Revolution. The family that owns the Château now has been there since their ancestor purchased the land after the original château burnt down. Of course not. My ex-proprietor and her sister are elderly (and I adore them and am still in contact with them!) and are sadly and probably the last of their family who will inhabit this place. They have told me amazing things. Growing up, there was a family of 12 and a staff of I don't know how many, but it was a working farm and supplied all of its own needs, so the staff would have been considerable. Claire told me that there was a sit-down lunch and a sit-down dinner, both formal, involving tablecloths and serviettes for everyone present, the family and any guests, and that each time the linen was crisp and white and starched. And then she told me that wash-day was once a year, so it was more like wash-month, I imagine, but now you can see the enormous wealth involved for one of these grand houses, which must supply linens starched and perfect for at least 12 people twice a day 365 days of the year. And then there were the household bedlinens (I'm not including personal linens here although undergarments that I find frequently have initials embroidered on them as well). And then there were the staff linens.

In fact, the Château didn’t just have a linen-cupboard. It had a whole linen-room.

Claire's description of wash-day explained to me why many of the pieces I find have numbers in the corners. Whilst the intricate monogrammes and hand-embroidered intials designated wealth, or at least some means, however scant, serving linen is most often found with red cross-stitched initials and frequently with numbers in the corner. These numbers represent how many pieces were in a set, so that, for example, if your wash month involved hundreds if not thousands of pieces, at the end, when the poor laundresses were ironing using a flatiron heated directly on the stove, and a large table covered in felt as an ironing board, they would know how many pieces of each were in a set, and at the end, everything would be tallied and stacked and put away in the enormous linen cupboards.

It wasn't just serving linens that have these red cross-stitched initials in the corner, I find them almost always on the farm-grown, handspun and handwoven hemp and linen tablecloths used on the vineyards here. This was more a case of marking ownership, during harvest there would be a large number of people working at any one time on the vineyards, often itinerant workers or neighbours, and these tablecloths would be spread out on the trestle tables to feed the armies of workers. You would want to keep tabs on your linen and hemp here too, because they represented a huge investment of time to grow, process, spin and weave. The value placed on these items can be seen by the respectful way in which many of them that fall into my hands have been repaired. It is even more obvious in the grain-sacks I find, made of the same handspun hemp, they frequently have beautiful repairs involving careful window patches. They were too precious to simply discard, and they too frequently have initials on them.

The intricate monogrammes on the linens of wealthy households was very rarely done by anyone in the house. Instead, it was sourced out to piece-workers, highly-skilled women, poorly paid, who would embroider these magnificent pieces, working often outside their cottages in all weather for the light it afforded them, as there would have been no electricity in their homes. For women living in times when there was no social security, and when many of their men-folk were killed or injured fighting in the wars that France was involved in from the 18th century onwards, this was one of the few ways they could earn enough to eat, especially whilst looking after young children.

After the First World War, with its fantastic loss of life and devastation of so many rural households, embroidery became even more important for rural women. It wasn't until the aftermath of the Second World War and the emergence of a beginning of social security that this kind of poorly-paid piece-work began to disappear. I'm not sad it's gone, as much as I marvel at the skills of these women, I hold always an enormous respect also for their bravery and their courage in doing what had to be done, in conditions which must have often been tough and which barely earnt them a living wage. When I hold a piece of very fine linen with very intricate embroidery, my mind doesn't turn to the owner, it turns always to the embroiderer. They were very rarely the same person, and the romantic notion of a young wealthy woman making up her trousseau does not fit the reality when you can see above that a large household would have used thousands of these pieces in a year. This is not to say that young women never embroidered their trousseaux, but the majority of pieces I find which I think fall into this category of embroidered linens were done by farm girls or lower middle-class women, I can tell from both the quality of the embroidery and the quality of the fabric used. Upper-class women would have more likely spent their time embroidering something purely decorative and very delicate. I love these rustic trousseaux when I find them, I always think I can feel their energy, their hope and care from someone whose hope in life was for a family, a safe place, food in their bellies and a fire in the hearth. I have this same hope, always, I think of them in comfort.

Towards the late 19th century, the rise of semi-industrialised piece-work meant that you could go and buy trimmings from places like Le Bon Marché, and didn't need to engage someone in person. Nevertheless these trimmings were mostly hand-done, and I find not a few of them with their original labels still intact, all completely handworked. Occasionally I also find pre-embroidered initials, often very beautiful, but quite simple. You would buy the necessary initials and then employ someone, or even yourself, to tack them securely onto the linen, and bingo, instant embroidery! There is also a rise from this time of professional businesses of embroiderers, as I find the same patterns and initial design repeated over and over again in linens dating from around 1910-1930. You would buy your linen sheets from a shop, or you would buy the fabric for the sheets, and then take the sheets or fabric to a business which specialised in embroidery, and choose the design from a book. The design would then be stencilled onto the linen and embroidered for you. Le Bon Marché also sold pre-stencilled ready-cut pieces of linen. All of the above meant that in the first decades of the 20th century there was a slight democratisation of embroidered linens, but not too much. All the work was still done by hand, and those hands were not paid at all well.

I get asked sometimes for particular initials, a request which I can't often fulfil as it is simply too difficult to keep tabs on such requests and the time required to propose individual pieces is not possible. For me personally, although I do have a couple of pieces with my initials (including a lovely huge damask tablecloth and its complete set of 12 serviettes), I just am always moved that someone, rich or poor, took the time to mark these linens so beautifully, because it is a tangible reminder of how much textiles were valued, even 60 years ago, and this is something I am continually advocating for and that I wish we would return to, minus the exploitative labour component. Yet again a reminder to think carefully about your cloth.

Housekeeping!

Lovelies, I have temporarily paused paid subscriptions. I am a little bit desperately cold in my house at the moment, as we wait for a stove that was ordered months ago but has been held up, to arrive and be installed. I am making the best of this situation by helping with the labour of tearing up the old attic floor to put insulation between the rafters and then put down a new floor - currently there is no insulation at all between the roof and the second storey, and nights are frigidly cold in this time of -5 and-6 degrees (it is 6 degrees in the kitchen regularly and I am having to warm the olive oil to get it out of the bottle). At least physical work keeps me warm, and then I am exhausted and can go to bed. I’m not in the least depressed by the current situation - it is temporary and this is my house and it will be warm, and I have shelter and peace - but it is affecting how I work (as is the absence of a laundry and a clothes line!)

I am also thinking a lot at the moment. I have put a bunch of stuff up on my website - currently everything on there is sale items and I have closed down all the other categories (except, weirdly, ‘paper ephemera’ because Squarespace had a fit and won’t let me!) and I might give the website an overhaul shortly. But this week I have several days of being a lumberjack and then a trip north to the dentist. Anyway I have added some wonderful linen sheets and table-linens to the sale on my website, and next up will be the last of the sale clothes. I’m a little off instagram this week but not entirely - I actually think it is far more important to remain on there watching than it is to participate in a boycott. I might go into this in more depth soon, because I feel like there is quite a lot of internet literacy missing amongst us and I might just share a little on what I know and why I move like I do.

Lastly, thank you to all of you who have donated to my raffles over the last seven months. Don’t doubt that we really did make an impact. I am not done - I am sure more help will be needed, either by Abdalla and his family or by another Palestinian family, and we will keep going. I have spoken to Abdalla since the ceasefire took effect - he is ok and he is pretty happy and relieved and I won’t ask him much - I imagine he and all Gazans have an enormous amount of pain and sadness to digest and sit with.

We cannot undo what we have seen in the last 15 months - if you are at all human it will have irrevocably changed you - but we can use our new-found knowledge to keep showing up in solidarity. These coming years are going to suck bigtime, there is no escaping the reality, no amount of pretty photographs or waffly romantic text is going to change that. Don’t be bamboozled, community is all we have.

xx Hanna

Only doing washing once a year sounds tempting … 😂 Do you think it was to do with water availability or best time of year to dry everything? So interesting

I have a few monogrammed linens from the Paris flea market & I loved reading about the history behind these stitches. I too wonder about whose hands made the stitches and what they thought about while they made their mark. Thank you. I also feel chilly reading about your chilly house!