Bird fabric

A little bit on how I work, how I think, and how to love imperfections, with the usual small forays off-topic

A lot of my time uploading stuff onto my website is spent simply photographing and describing the faults. Over the years I’ve been asked many times - do you have something similar but without stains/holes/imperfections - as though I was buying things wholesale and could just order some 150-year-old textiles in perfect condition. One time someone asked me if I could get the same gown but in a size 16, which was very cute - I don’t think the asker had realised it was an antique! Sometimes I imagine what I would do if I could time-travel - how I would run back to the 1780’s and buy every last piece of printed textile I could, or buy up all the handwoven Bengal muslin and Empire line dresses and 1820’s gowns I could find, or back to the 1930’s and buy alllllllllllllll the chiffon silk clothing on offer. But where would I store them so I could find them intact when I time-travelled back to the now? Where would stay safe and dry and clean and dark for 100 years, let alone 250?

The fact is that every single piece that comes through my hands has some little issue. Yes, even deadstock fabric and clothing (deadstock means ex-shop-stock that was never sold). Even those most perfect of old pieces have storage marks, or foxing on the edges.

I got married the first time in Istanbul in 2002, and my wedding dress was handmade for me by a professional tailor with six fittings (It was based on Caroline Besset-Kennedy’s wedding dress, and it still fits me and it is still absolutely gorgeous and looks far more like a sleek cocktail number than a frilly wedding dress). The silk came from a very old shop on the Asian side of İstanbul. This shop had a ground floor with the usual (very beautiful - Turkey is an amazing place for the textile lover) textiles, but the second floor was full of stock that dated back to the 1930’s and 40’s. And these rolls, stored as they had been in a clean dry stable environment not subject to bright direct sunlight still had foxing (oxydisation marks) at the ends where the rolls stuck out of their shelves.

This is just what happens - it has to be accepted. Oftentimes those storage marks will lift out easily enough - I find them on pretty much everything I buy that is more than 40 years old.

I wish I could show you my shoes. They came from one of the oldest shoe shops in İstanbul and they were red suede (go ask a Turkish friend why the bride wears a red belt - I didn’t qualify and so I wore red shoes instead!). I wish they still fitted me, but two children later my feet are like snowshoes by comparison! They are so beautiful I display them sometimes! They lasted far longer than the marriage.

And here I come to this piece. Or pieces. These I believe are early on in the 19th century. I am basing that from my (fairly scant - this is not my area of expertise but I have spent several decades now paying close attention to textiles of all sorts) knowledge of printing methods, colourways, and composition throughout the period from the late 18th century to the mid-20th. This one is both gravure-printed and block-printed - both of which were in use at this time (I am going to give this one a date of 1830 for the sake of it), and the colour-palette is fairly limited and contains only shades which could have been derived pre-coal-tar dyes. As soon as coal tar dyes became commercially available from the 1860’s onwards, the uptake was huge and the businesses specialising in dyeing cloth naturally must have collapsed almost overnight. Coal-tar dyes were massively cheaper and less time-consuming than natural dyes, and much easier to handle. The process of making turkey-red, for example, using natural sources, was unbelievably complicated and took weeks, and it remains a colour that not many modern natural dyers will venture to recreate. The vat dyes like pastel (woad) or indigo demanded an expertise that could take many years to master to get a deep even colour, and even the simpler dyes like weld or madder required huge amounts of raw materials for a commercial dyehouse, as well as an enormous amount of physical work. And then to get composite colours like green, turquoise or purple - let alone to get them on vegetable fibres, which most natural dyes don’t take to so easily….my gosh it was work. It was no wonder that most poorer people went about in fairly basic colours - the natural colours of linen and hemp and wool supplemented with a little bit of purchased colour, usually red.

(As an aside, I often wonder whether the red stripes at the sides of traditional French linen teatowels are a hangover from this tradition of buying a little bit of commercially-dyed yarn to provide a slight variation in the usual cream, ecru and oatmeal shades of handwoven linen and hemp which I see often in 19th century kitchen textiles. Does anyone have any knowledge about this?)

Anyway the above should amply explain why I think this textile is very old. Why, if you could reach for purple, bright blue, deep yellow, or acid green with just the tip of a bottle, would you restrain yourself to the beautiful but austere colours of these pieces? Granted that some of the colours have faded over time - if there was any yellow it has probably gone by now, the browns in this piece may once have been purples.

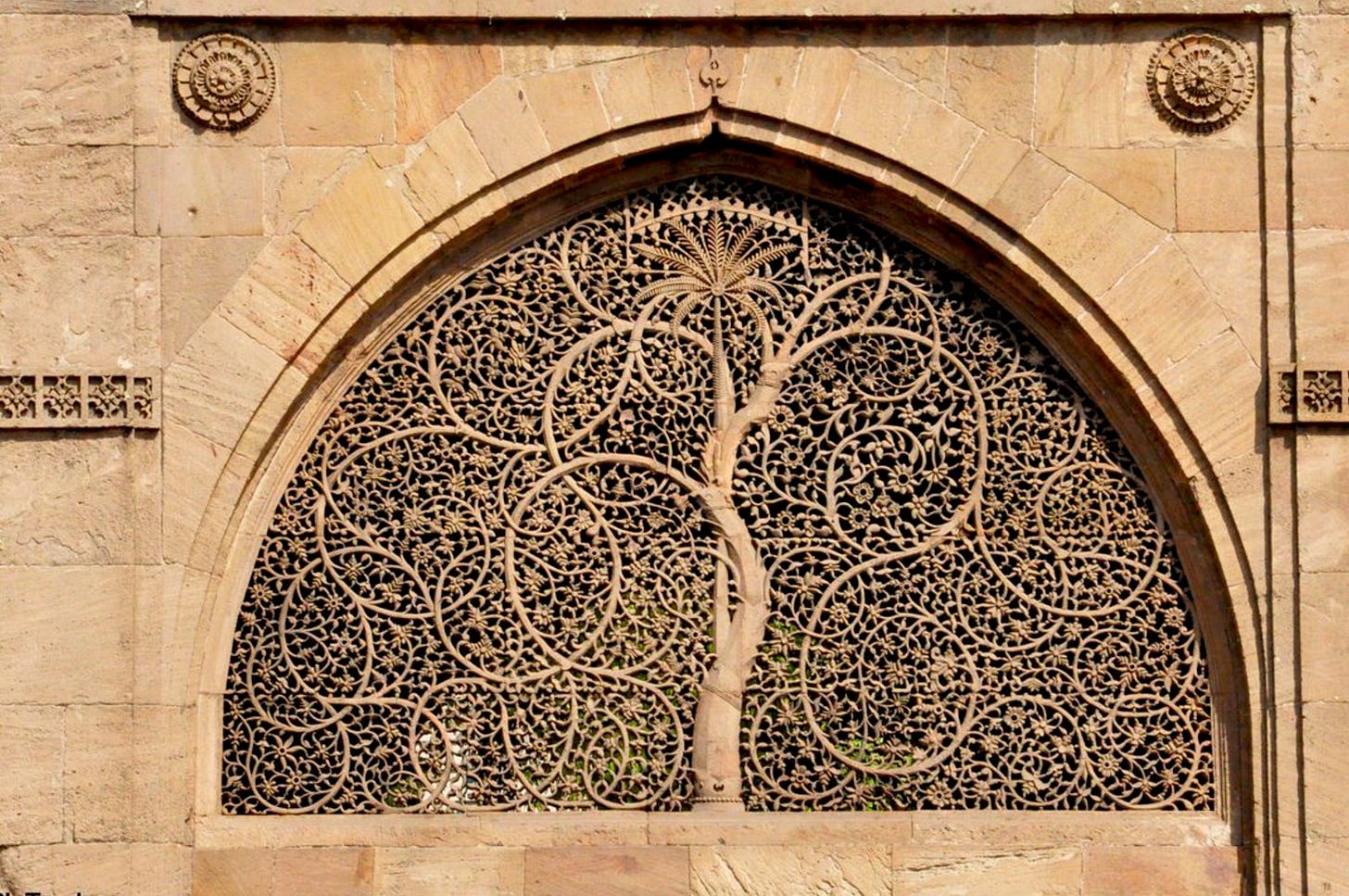

Lastly there is the design. This is a clearly Indiennes-inspired piece, and it’s quite a funny mix of styles if you look closely. The red flowers and the bird could almost have leapt from the beautiful and incredibly sophisticated textiles of the Indian subcontinent, what is today modern India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, which Europeans so admired and lusted after that they finished by stealing the techniques used to create them, as there was nothing even remotely similar or sophisticated in the way of printed fabrics in Europe at this same time. The finely drawn stylized flowers are also deeply inspired by these fabrics, but seem to be slighty more Europeanized - there are daisies in there. But that central motif of a tree-like sparse branch has absolutely been copied from a Tree of Life, of which my favourite ever example is this one here, from the Siddi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad, India, built in the 16th century by and for the African diaspora community in that great city, and one of the most beautiful windows anywhere in the world to me.

I nicked this from pinterest but couldn’t attribute it - I am sorry to whomever it belongs to for the theft. I based the design of the packaging I used for my first business, which was run between Oman and Australia and specialised in frankincense, partially on this stunning window)

Actually lastly lastly there is also the fact that the seller, an obsessive collector and hoarder of fabrics of all sorts, said to me - this one is very very old. So there’s that as well!

Ok so now I have run through all the ways I use to locate this piece in time, I want to go back to the start of this little essay. Look at the discolouration on these pieces. This is oxidisation, but not just from several decades - this is at least a century. Probably these pieces were stored in a wooden trunk - they have been unpicked from a piece of furniture, that much is clear, because their sides have the holes and staining which indicates that metal tacks have rusted onto the fabric and eaten into it, but it lacks the stains which I always find on old, used mattress coverings (remembering that apart from sleeping and sex, women used to give birth at home on their beds - it always makes me grin a little bit when people ask for unstained mattress ticking as there is rarely such a thing unless it is deadstock, and I’ve never come across deadstock mattress ticking that was older than the 1930’s!). And it also lacks the uneven fragility of bed or window curtains - almost always with both bed and window drapes there will be one area which was exposed to the sunlight more than the rest, which will be slightly faded, badly faded, or even falling to bits depending how exposed it was and for how long.

No, I think this was a sofa or chaise-longue covering in a wealthy household. And when it was unpicked, maybe 150 years ago, somebody thought - oh, that’s pretty, I’ll make something out of this, but I haven’t got time at the moment, I’ll just stick it in this wooden chest until I get some time. And there it stayed. And we all know this little manoeuvre, we are all guilty of it, and I not infrequently find other things that I am sure have been put away for ‘when I have time’, or ‘when the occasion is right/when I get married/when I stop being pregnant or breastfeeding’, and there they stay! Use your stuff now, lovelies, because you’re a long time dead and some of my finds prove it!

Before I washed these pieces the oxidisation was really intense, a very dark brown, almost looking like rust. This is why I am sure they were stored in a wooden chest - well, also because honestly what else would you store something in 150 years ago? Wood emits gasses which interact with the oils and dirt in textiles and can really seriously stain fabrics, and also weaken them over long periods These seem to have been stored pleated or crumpled - the exposed edges oxisided, the interior parts remained relatively clean.

I soaked these in a very mild solution of percarbonate soda and gentle organic washing liquid, and I checked on them regularly, manipulating them in the soak-bath. I was watching to see that the colour did not leach out - many old dyes, both organic and chemical, can react to the alkalinity of percarbonate and of soap - in my experience the chemical dyes are far more unstable than older natural dyes. My particular dislike is the black used to dye clothing from the 1870’s to about 1930, it is toxic and disgusting, it runs, it smells, it causes the fabric dyed with it to disintegrate, and for this reason I tend to avoid just about everything black.

Actually I tend to avoid everything black even now unless it is extremely good quality. Even, and especially, in modern clothing, the darker the dye the more toxic it is. All those cool stylish inner-city types in their head-to-toe black probably have overloaded livers. Do not discount the amount of toxic dyes your skin can absorb, and how those chemicals can stay in your body. Yet another reason to wear second-hand, where somebody else got the bulk of the toxicity before you!

I digress. Back to the birds. I washed these very gently, and then hung them out in the mild late autumn sun, on one of the last days when the sun decided to make an appearance. The oxidisation faded quite considerably, and the soak water was nice and brown to prove it, but it didn’t entirely come out.

And here I stopped. The colours in on these pieces are still singing to us, beautiful and jewel-like. The textile itself is sturdy. Objectively it is beautiful. But if I aim to get it perfect, I may finish by ruining it entirely. Either we can admire it for what it is now that the passing of time and the elements in various manifestations have left their imprint - or we run the risk of losing it completely.

In different spheres of my life I have had to accept this philosophically. For most of my life I have preferred the old to the new. For some of that time it hasn’t necessarily been a choice; being poor teaches you to get comfortable with imperfection. But for at least two decades now, even now that I have a comfortable enough life, second hand and antique is my preference, my go-to, long before I try to find something new, I will try to find it old, and so of necessity I have learnt to accept imperfections. In fact, I have learnt over the years to not just accept them, but to elevate them. In French there is a verb ‘sublimer’ from which we get the English word ‘sublime’. But the French verb has no modern single English equivalent word - it is literally - to make sublime, to elevate. For me, old things with patina have been made sublime.

Just today I had a discussion with the regional representative for a brand of organic house and cavity insulation. I want to use his product, but I need to know the best way to insulate my attic. The attic of my house is 100 years old. He asked if I planned on removing the ceiling and replacing all the rafters. He said the ideal method would be to do that so that I could lay down the vapour-break underneath the rafters. I raised a figurative eyebrow over the phone-line and replied “At some point I think we have to work with what is at hand, and we need to adapt the process to the reality of the house, which is not a new build and can never be”. The man I was speaking to rapidly backtracked - he realised that what he had suggested was really a bit ridiculous. Removing the rafters from this house runs the risk of doing extensive damage to the old lime mortar and stonework. Once again - accept the imperfections and limits, adjust your expectations to fit reality.

We even have to learn to do this in relationships. I have been thinking about this a lot lately, acceptance of the way people are, the way they cannot or will not change, the way if you push them too hard, or if they push you too hard, the relationship breaks - the way you must either take them as they are or leave them as they are. I often think of this as a bit Zen, I don’t know actually if it is - but just get with the truth and accept it and adapt as necessary, or walk away if it’s too hard, and if you can’t, try to find the beauty in what is.

And so it is with textiles. You can see more details of these pieces on my website. If nobody buys them they will probably go back into a wooden trunk.

{Please don’t forget my raffle that was outlined in my last post. I’ve had a really good response, some people have written to me thanking me for organising it but I want to thank you for continuing to be here with me. Together we are trying to keep a family safe and fed and through this bloody thing and to help them rebuild as soon as possible. Imagine if we can do this together and then we can go meet them. Hold that thought and go see the last post and don’t forget to send me a screenshot if you want to be entered in the raffle which will be drawn next Tuesday evening Paris time. Thank you lovelies, with all my heart}

xxh

I am not experienced in dating fabric prints, but I can imagine that fabric used in a late 18th century round gown - they sometimes appear on older women in Jane Austen shows, as older women tended to wear the clothing of their youth.

As to black - there's one black fabric you can safely use, and that's black wool used to make nun's habits. They were - may still be - woven from the darkest wool possible, then lightly overdyed in black. Sheep don't come in black - the closest is a very dark brown - but it doesn't take much dye to get it black. Alpacas have a true black, which is gorgeous. Apparently there were special flocks of sheep kept just to make nun's habits!